Drawing In the Museum – Drawing Out Ideas

Nicola Wallis works at the Fitzwilliam Museum as a Practitioner Research Associate in Collections & Early Childhood. For the Art Educator blog, Nicola explores the rich potential of drawing and the Fitzwilliam Museum's early years programme.

Image 1: The Fitzwilliam Museum

Here at Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum we have a world-renowned collection of over half a million beautiful works of art, masterpiece paintings, and historical artefacts from antiquity to the present. Our early years programme welcomes young children to explore through stories, songs, play and creative expression. We know that children’s engagement with, and exploration of, museums is multisensory and multimodal, spanning the ‘hundred languages’.

In this article we’re focusing on the potential of drawing; drawing, however, is not seen as an isolated form of activity, but rather one manifestation of children’s physical, cognitive, social, and emotional experiences. In how we work, we try and build senses of connection, curiosity, place, and identity. We hope that our reflections on our engagements with young children will contribute to insights into how other museums, collections, and attractions might also engage their young visitors.

Inspiring surroundings

When children are invited to draw in the museum environment, their identity as unique creators in the present moment is acknowledged. They can explore and develop their ideas about what they are seeing and communicate these through the visual language. However, it also connects them with makers from the past, whose work they are surrounded by. This offers an alternative to the constant pressure of the ‘next step’ felt by many early childhood educators in England currently.

Encountering Armour

During an extended engagement project for families at the Museum, children were invited to explore armour. Although it was not possible for them to touch it, they investigated the shapes and textures through careful looking, photography, playing with metal objects, and of course, drawing.

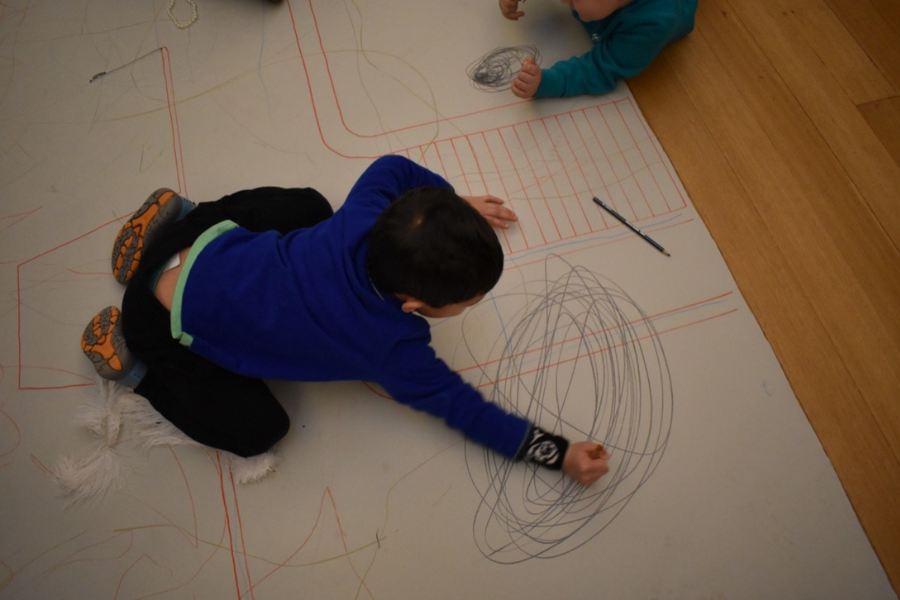

Image 2: Children responding to the armour through drawing

They respond to the straight lines and sharp angles they can see by recreating these in their own work, and investigate the sense of enclosure of a full suit of armour by creating shapes that are completely encircled.

Image 3: Emma’s photograph of armour for a horse & knight on display in the gallery

Image 4: Emma imagines the feeling of being inside a suit of armour through her drawing

Emma said, ‘it covers your face up, it covers your eyes up, it covers your tummy up,’ as she used coloured crayons to colour in the different sections of her drawing.

Noticing these responses to the physical aspects of the objects on display reminds us of the physical nature of children’s drawing. The sensation of crayon on paper on the gallery floor; the sounds created by the marks being made and voices echoing off the cases and high ceilings; the awareness of their bodies in the space and the sense of scale this brings are all part of children’s experience of drawing in the gallery. It is not an activity that happens in isolation, but with connections to the people and objects all around them, and beyond – to the makers, owners, and users of these objects in the past.

When working in an unfamiliar environment such as a museum, it can be tempting for adults to set narrow tasks or direct children’s attention based on what we assume will be of most interest to them. Offering children tools such as drawing allows them the time and autonomy to find their own most significant connections, exploring and communicating their ideas and fascinations.

Drawing to gather and build relationships

As well as a way for children to discover their personal connections with the objects on display in museums, drawing can also be collaborative. When carried out as a shared activity, drawing can be a form of collaborative meaning making inviting multiple ideas and perspectives. This is particularly appropriate in the museum environment where all kinds of objects are brought together to tell a story about their history, or a shared theme.

Having shared a familiar picture book with a group of children, we extended the story by bringing in additional characters and activities based on the ceramic objects and porcelain figurines in the gallery. Children and adults drew together on large paper taped to the floor.

Materials such as lengths of string were offered for more transitory mark making, alongside pencils. In fact, some children chose to use the pencils as loose parts objects to create with in preference to drawing with them.

Image 5: Creating a story through collaborative drawing

Although the group had all shared the story in the gallery together as an introduction, no final aim or outcome of the drawing was discussed. Instead, children and adults watched each other – some keen to tell a story or try out ideas through their drawing straight away with others holding back and observing. Ideas began to collide, sometimes literally with pencils bumping into each other, and sometimes as thoughts and motifs were expressed, noticed, and expanded on by the artists - children and adults together:

Joseph: ‘an owl’s coming!’

Nicola: ‘I can see it swooping! It’s coming after me!’ [Joseph’s pencil chases Nicola’s pencil across the page]

Ivy draws a curved line: ‘Get in this cave!’

Nicola moves her pencil behind the curved line: ‘We’re safe in here.’

Ivy presses her pencil down hard on the paper and scribbles dark lines. ‘It’s dark in here.’

Joseph draws two smiling faces: ‘Here’s me and my mummy. Did you know we went to a wood, and there was a Gruffalo you could play on and a slide?’

Ivy slips her pencil diagonally downwards, leaving a sloping line, and then repeats this a couple of times. ‘My mummy’s on the slide too!’

The resulting drawing was less important than the shared process of creating it together. This was an opportunity to develop personal relationships through listening and responding to each other, and also to establish a group identity as the creators of a shared experience.

Informal environments such as museums provide ideal opportunities for adults to drop their role as leaders, and instead to become co-learners and contributors. In shared activities such as collaborative drawing inspired by our surroundings, adults can pay attention to becoming an active, listener, and responsive participant, rather than a director of the learning experience.

Straight Ahead! This Way!

We have also observed children using drawing in the Museum as a way of coming to know a place and establish their relationship with it. This is particularly important in unfamiliar surroundings such as museum or gallery spaces, but can be a useful tool anywhere that children are seeking to create a feeling of belonging and ownership.

The impact of being able to leave a mark on a place, even if it is removable or temporary, should not be underestimated. This is a powerful way for children to explore their relationship with a place and to communicate their sense of belonging.

This triangular relationship between child, place, and mark making can often manifest as an interest in map making. This might be particularly relevant in a museum context where maps and floorplans are readily available for visitors to read.

At the Fitzwilliam Museum, when working with groups of children over a sustained period, we have observed a fascination with map making which we have enjoyed exploring alongside them. Some of these maps have first been created using the body:

‘With a rolled-up piece of paper, reminiscent of a treasure map perhaps, 3 year old Andrew took the lead in our group, consulting his map and telling us, ‘straight ahead! This way!’ When invited to draw in the galleries, Andrew created maps of adventures that he imagined happening there. His drawings showed not just locations, but also movements and encounters happening in the space.’ [Museum Educator Fieldnotes]

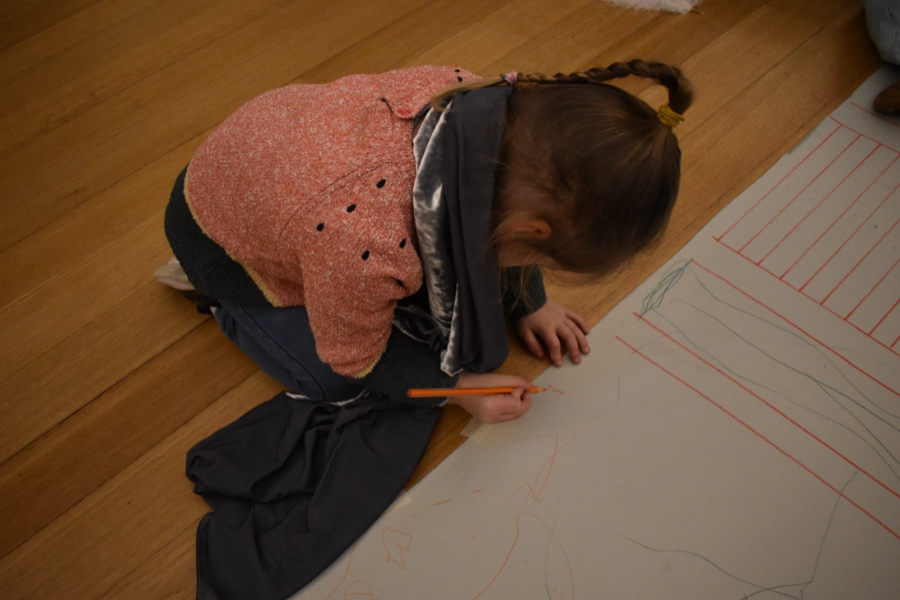

Other children responded to Andrew’s map making and his commentary on it, and adults supported this interest by inviting the children to create large floor map of the Museum on which they could document their experiences and try out ideas. The red lines that can be seen in the images below show a gallery floor plan drawn by one of the Museum Studio Artists involved in the project. Children were invited to develop this floor plan by drawing their movements and activities in the gallery onto it, and many added additional features too.

Joseph said, ‘I’m drawing a room.’

I asked, ‘Is it one of the rooms in this Museum or is it from your imagination?’

Joseph told me that it was from his imagination. He made a series of parallel lines like the ones that the adults had drawn to represent the main staircase and told me that these were the stairs to get in. He then drew a ‘triceratops’ and a ‘bench’ next to it, explaining to me that this was where the people could sit to look at it. [Museum Educator Fieldnotes]

Some children drew tiny dots representing their footprints climbing up stairs into the gallery, while others drew long lines and spirals reminiscent of the ways in which they had moved around the room itself:

Lee says, ‘I’ll lead us all the way…’ and draws a line from one edge as far as he can towards the other side until colliding with Andrew’s drawing. He starts another line and says, ‘all the way!’ again.

Andrew is narrating as he draws: ‘he’s gone all the way out there now.’

Lee continues drawing a long line to the edge of the paper saying, ‘And then all the way back home.’

Elizabeth looks up from the bottom corner of the paper, indicating the other side: ‘all the way up there.’ She draws a line and Fran follows. Elizabeth chants, ‘all the way, all the way, all the way up there,’ and stops at the red pen line that represents the gallery wall. She repeats this a couple more times. [Museum Educator Fieldnotes]

Their teacher reflected:

‘What was really enlightening was how the children engaged in the mark making activity, trying to make different kinds of marks to represent running, quiet, etc. Fran, Ivy, Susie, Andrew, and Lee were a real surprise as they don't normally engage in that kind of thing and Andrew and Lee are not generally interested in drawing or mark making at all.’

Image 6: The children describe the Museum by creating a large-scale map of the gallery

Image 7: Adding large movements to the plan

Image 8: And small details

A concluding reflection

When adults pay close attention to children’s interests by being willing to learn alongside them, they will be able to respond creatively and extend children’s fascinations, such as making maps to represent their interactions with spaces. However, just as important is the fact that sensitive, responsive invitations demonstrate to children that they are being listened to and heard, and that their interests are important and valuable.

Children’s drawing, both in the museum context but also elsewhere, can be a means of social interaction, responding to the environment, and communicating a sense of personal identity and belonging. When adults are aware of the multi-layered nature of drawing activities, they will be in a better position to support children’s meaning making and explorations in the graphic language. By offering opportunities to draw in different environments such as museums, we can build on the use of drawing as a tool for research, documentation and together.

About the author:

Nicola Wallis works at the Fitzwilliam Museum as a Practitioner Research Associate in Collections & Early Childhood. She is interested in art and cultural experiences for young children and the links to democratic engagement and social justice. She has previously worked as a primary and nursery teacher and has post-graduate training in both Museum Studies and Early Childhood. She is currently studying for a PhD with the Centre for Research in Early Childhood focusing on very young children’s engagement with objects and spaces.

Article Editor: Robin Duckett, Director, Sightlines Initiative

Image credits: the Fitzwilliam Museum